The gentle curl of incense smoke has been a companion to spiritual practice for centuries. Walk into a meditation space or sacred temple and you’ll likely catch the soothing aroma of burning sticks – whether it’s a bundle of sage, a slender joss stick, or resinous frankincense. Spiritual sticks, like all other forms of incense (when natural and high quality), have a remarkable ability to calm the mind, cleanse negative energy, and set the stage for prayer or mindfulness.

But with so many options out there, how do you choose the right incense for your needs? This comprehensive guide will demystify spiritual and joss sticks, explain how to use them for meditation and cleansing, and help you find the best products – with an expert eye on quality and authenticity. We’ll also shine a light on one outstanding choice that stands above the rest for a truly sacred experience.

Limited Offer: Save 25% when you buy 3 or more packs of Real Frankincense Incense Sticks at KohẓenOfficial.

What Are Spiritual Sticks, Joss Sticks & Natural Incense?

Spiritual sticks generally refer to any incense or herb bundle used with spiritual intention. This could mean traditional smudge sticks (like sage or palo santo bundles) burned in cleansing rituals, or simply incense sticks marketed for meditation, healing, or even manifestation. (In fact, a recent product line has popularised “Spiritual Sticks” labelled for goals like money, sleep or confidence – essentially incense with big promises.) At their core, however, spiritual sticks are tools to focus intent and create a sacred atmosphere through scent. It’s not the logo on the box that makes an incense “spiritual”, but the way you use it in your practice.

Joss sticks, on the other hand, are essentially incense sticks by another name. The term “joss” comes from a pidgin English word for deity, reflecting the sticks’ traditional use as offerings in East Asian temples. In Chinese and Indian cultures, incense sticks (often called agarbatti) are burned before altars and shrines as a sign of reverence.

A joss stick is typically a thin stick of incense (sometimes with a bamboo core, sometimes solid) that you light to release fragrant smoke during prayer, meditation, or ceremony. In short, joss sticks = incense sticks, especially in parts of Asia where they’ve long been integral to spiritual life. If you’ve ever lit a stick of sandalwood or Nag Champa and watched the smoke waft upward with your wishes, you’ve used a joss stick.

Natural incense simply means any incense made from pure botanical ingredients – woods, resins, herbs, oils – rather than synthetic perfumes or chemical fillers. High-quality natural incense might take the form of sticks, cones, loose resin, or smudge bundles. What matters is that it’s derived from Mother Earth: think frankincense resin tapped from ancient trees, cedar and sage gathered for their cleansing power, or hand-rolled sticks using only plant-based binders.

You can find our full range of Natural Frankincense Products at KohẓenOfficial.

Natural incense tends to have a richer, more authentic aroma and cleaner burn than cheap drugstore incense that might be doused in artificial scents. When you’re seeking a spiritually uplifting or healing experience, you’ll want to reach for natural incense sticks over the bargain petrol-station variety. The difference in purity and vibe is night and day.

In summary: Spiritual sticks is a broad, modern term for incense used in mindful practices; joss sticks are traditional incense sticks (the same thing by a cultural name); and natural incense denotes quality, plant-based products without the chemicals that can mar your experience. Now that we’ve clarified the basics, let’s explore how these aromatic tools can enhance meditation and cleansing rituals – and what to look for when choosing the best incense for your own spiritual journey.

Incense in Spiritual Traditions: A Brief History

To appreciate why quality is key, it helps to understand incense’s sacred history. Incense – usually grains of aromatic resins, woods, or herbs that burn with a fragrant smoke – has been used by humans for thousands of years as a bridge between the earthly and the divine. The very word “incense” comes from the Latin incendere, meaning “to burn,” reflecting its early ritual use in temples and shrines.

Read More in our blog post about the Spiritual Meaning of Frankincense.

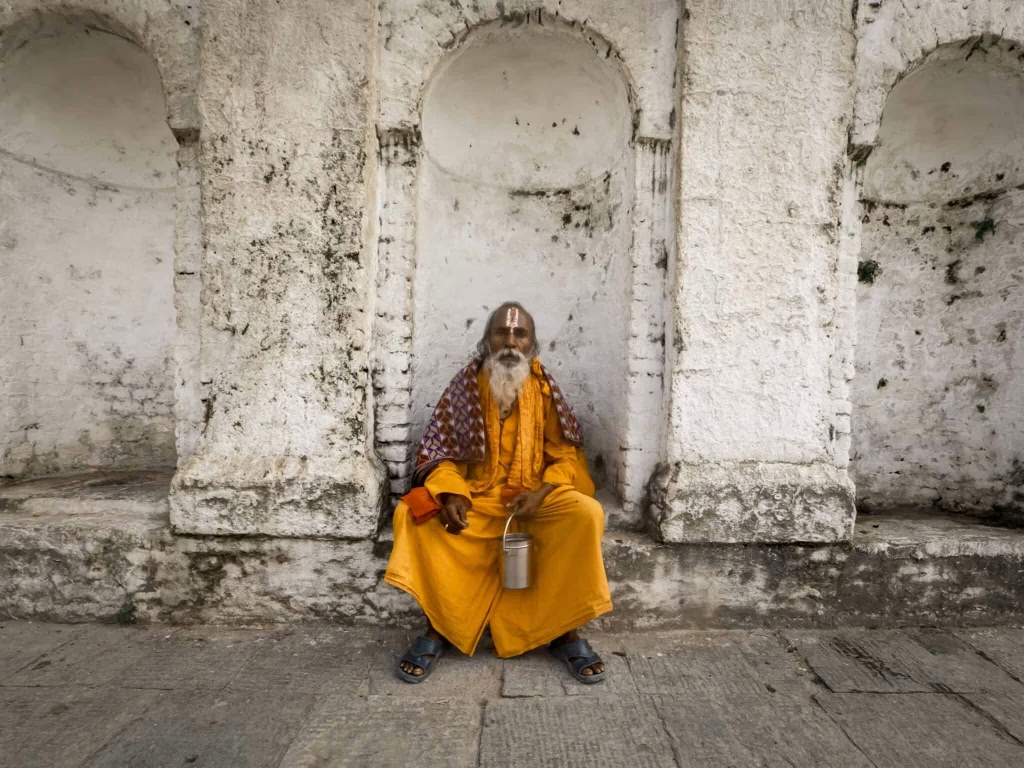

Across the ancient world, burning incense was a sign of reverence. In Egypt, priests offered resins like frankincense and myrrh to honour the gods, believing the fragrant smoke carried prayers to the heavens. In India’s Vedic ceremonies and later Hindu pujas, incense was (and is) offered to deities as a symbol of devotion and to purify the air. By 2000 BC, incense had also spread to China, where it became central to ancestral offerings and Taoist and Buddhist rituals. Thin sticks of incense (what many today call joss sticks) became especially popular in East Asia for their convenience and steady burn.

In Chinese culture, incense is so vital that entire festivals incorporate it. During the annual Hungry Ghost Festival in late summer, for example, families burn incense sticks and joss paper to appease restless spirits and honor ancestors. In these rituals, the gentle curling smoke is believed to convey nourishment and comfort to the unseen souls, showing how deeply incense is woven into spiritual life. (Imagine the evening streets of Hong Kong or Singapore during this festival, the air hazy with spiritual sticks sending up prayers and comfort for the departed.)

Japan too developed a sophisticated incense tradition. History records that incense wood first arrived in Japan around the 6th century along with Buddhism, and the Japanese refined its use into an art form. By the 14th–15th centuries, the samurai and aristocracy practiced Kōdō, the “Way of Incense,” turning the appreciation of incense into a ceremony as nuanced as the tea ceremony Japanese incense history.

Participants would heat precious incense woods and play “incense games,” guessing scents and reciting poetry. This wasn’t about masking odours – it was about experiencing incense with all the senses and an open spirit. Notably, the incense sticks we know today (bamboo sticks coated in aromatic paste) also rose to popularity in these eras, prized for their ease of use and elegant form.

Through these cultural lenses, one thing becomes clear: incense was always much more than a room fragrance. It was a ritual tool, a spiritual technology connecting humans with something higher. And the ingredients mattered. Historically, the finest incenses were made from pure resins like frankincense and myrrh, aromatic woods, barks, and herbs gathered from nature’s bounty – no petrochemical perfumes, no cheap fillers incense. When you burn what our ancestors burned, you partake in an ancient, powerful tradition. It’s a good reminder that choosing quality incense isn’t just about a nicer smell – it’s about authenticity and keeping a sacred link alive.

Find Out More about in our Ultimate Guide to Frankincense blog post.

Using Incense for Meditation & Cleansing Rituals

Fragrant smoke has been intertwined with spirituality for millennia. Incense in meditation is not a new wellness trend but a time-honoured practice spanning from ancient monasteries to modern yoga studios. The reason is simple: aroma has a profound effect on the mind and energy of a space. When you light a natural incense stick, you’re not just adding a pleasant scent – you’re setting an intention and atmosphere.

For meditation, certain aromas can help quiet mental chatter and deepen focus. For example, lighting a stick of pure sandalwood or frankincense before you sit down to meditate creates a gentle signal to your brain that it’s time to turn inward. The act of watching the wisps of smoke rise and dissipate can itself be a meditative focus. Many practitioners find that incense helps anchor their attention to the present moment – each breath you take is infused with a sacred fragrance, keeping you centered.

Frankincense in particular has been burned for centuries to invite calmness, enhance concentration, and even induce a prayerful mood. In fact, modern science suggests that frankincense’s aroma isn’t just placebo: a compound in real frankincense resin (incensole acetate) has been shown to ease anxiety and gently elevate mood in studies. No wonder churches and temples around the world have used frankincense smoke to uplift the spirit – and why you’ll often find people today burning it during meditation or yoga to foster a sense of sanctity and peace.

When it comes to spiritual cleansing, incense and smudge sticks are like a deep breath of fresh air for your space’s energy. Burning incense for cleansing is a common ritual across cultures: the idea is that the smoke attaches to negative or stagnant energy and carries it away, purifying the environment (and one’s aura) for a fresh start. Smudging with sage is one well-known example – the pungent white sage smoke is traditionally used by Native Americans to cleanse people, places, or objects of unwanted vibes. In a similar vein, waving the smoke of frankincense resin or palo santo wood around a room is thought to banish negativity and invite protection.

Ancient Egyptians burned frankincense in funeral rites to sanctify the space and guard against evil influences during transitions. Today, you might burn a spiritual incense stick with the intention of clearing negativity after an argument, or to consecrate a new home so it feels imbued with peace and positivity. The key is your intention: as you walk the incense through each room or around your body, visualize the curling smoke sweeping away stress, illness, or any heavy energy, leaving the atmosphere light and sacred.

A beautiful thing about using incense in these ways is the small ritual it creates in your day. Striking a match, lighting the stick, and gently blowing out the flame to let it smolder – this simple act can become a mindful ritual of letting go and refocusing. As the room fills with the natural fragrance, you may notice your breathing slow and deepen. It’s a sensory cue that you’re entering a different headspace, whether for meditation, prayer, or just a quiet moment with yourself. By engaging our sense of smell, incense provides a pathway to relaxation that complements the mental practice of meditation or the symbolic act of cleansing. It engages body and spirit alike.

Tip: Always burn your incense or smudge stick with care. Use a proper holder or fireproof bowl to catch ash (safety first!), and ensure some ventilation so you’re not inhaling too much smoke. A little goes a long way – you don’t need to choke on thick smoke to cleanse a space. In fact, the most pleasant incense experiences usually involve a gentle wisp of smoke that slowly infuses the air, rather than an overpowering cloud. Quality incense will burn with a subtle, steady smoke that carries the scent without setting off the fire alarm.

Learn More here in our popular blog post How to Use Frankincense Resin Like a Pro

How to Spot Quality Incense (and Why It Matters)

Not all incense is created equal. If you’ve ever been turned off by incense that smells like burning chemicals or left you with a headache, you were likely using a low-grade, synthetic product. Unfortunately, many mass-market “scented sticks” fall into this category – they might be doused in cheap perfume oils or even contain charcoal and saltpetre to force them to burn. These can produce acrid smoke and frankly do the opposite of what you want (who can meditate with stinging eyes and an artificial smell lingering?). Quality matters greatly when it comes to choosing incense for spiritual purposes. Here’s what to look for, and what to avoid:

- 100% Natural Ingredients: The best incense sticks are made from real plant-based materials: resins, herbs, spices, woods, and essential oils. If the package just says “fragrance” or has a chemical list a mile long, steer clear. Natural incense will proudly mention ingredients like “sandalwood powder, frankincense resin, botanical gums” etc., whereas inferior sticks rely on synthetic fragrances to mimic real scents. Always opt for natural incense sticks to ensure you’re getting the true aroma and vibration of the ingredients, not a lab imitation.

- No Charcoal or Hidden Fillers: Incense that includes charcoal or artificial binders can burn harsher and produce more smoke (and potentially toxins like benzene or formaldehyde in the air). A pure masala incense (made by rolling paste of natural ingredients onto sticks) or dhoop stick (solid incense without a core) will burn cleaner. You can often tell by the ash – a good natural incense leaves a fine, soft ash, whereas a synthetic stick might leave dark, sooty residue. High-quality incense also tends to have a lighter, natural colour (from the herbs/resin), not unnaturally bright or greasy-feeling sticks.

- Handmade or Traditional Craftsmanship: This isn’t a must, but generally, incense made in the traditional ways (hand-rolled in small batches, often by artisans or monks) has a certain quality and intention imbued in it. When incense is made with mindfulness and prayer, it carries that energy. In contrast, mass-produced incense from factories can feel “empty” or inconsistent. Look for brands that are transparent about their sourcing and process – for instance, incense coming from a monastery, or a family that’s been making incense for generations, or a company that directly sources from indigenous communities. This usually indicates a higher level of care in production (and often more ethical sourcing as well).

- Aroma Profile: Trust your nose. Quality incense will smell pleasant even before lighting – you might get a hint of its character when you sniff the unlit stick or cone. If it smells like synthetic perfume or is excessively strong out of the package, that’s a red flag. When burning, natural incense gives off layered, nuanced scents. For example, a true frankincense stick might start citrusy-pine, then reveal a honeyed amber note as it burns, and leave a gentle sweetness in the room after. A fake “frankincense-scented” stick, by contrast, might just have one flat perfumey note all the way through (and it usually doesn’t smell anything like real frankincense tears burning). Authenticity of scent is a giveaway: if it smells like the real herb or resin (even in a subtle way), it’s likely natural; if it smells like a cologne or “air freshener”, it’s likely doused in fragrance oils.

- Burn Performance: Top-notch incense will burn evenly and for a decent duration, producing pale or white smoke rather than a thick black plume. It shouldn’t irritate your nose or throat. Many cheap sticks burn up too quickly or give a chemical whiff as they go – not enjoyable, and not great energetically either. A quality stick might burn slower, and you can even stop and relight it later without a nasty char smell (a trick that inferior sticks often can’t do – they’ll smell awful if you try to relight halfway). Consistency is also a sign of quality: one stick to the next should smell and behave roughly the same. If one batch of your incense smells radically different or some sticks fizz and others don’t, it’s a sign of low-grade manufacturing.

Why does all this matter? Because if you’re using incense or smudge sticks as part of your meditation or cleansing routine, the last thing you want is to introduce toxic smoke or jarring scents into your sacred space. The incense should be supporting your practice, not sabotaging it. High-quality, natural incense aligns with the very purpose of these rituals: it’s clean, healing, and conducive to relaxation. Meanwhile, poor-quality incense can create chaos – energetically and literally (imagine trying to “cleanse” a room with something that leaves a chemical smell; it’s counterproductive). Think of it this way: if you’re investing time into spiritual self-care, it’s worth investing in incense of equal calibre that enhances the experience.

Lastly, be aware of marketing gimmicks. As mentioned, some modern products sell “spiritual sticks” claiming to attract money or love magically. It’s wise to approach those claims with skepticism. Incense can certainly support your intentions – for instance, a soothing scent can put you in a positive mindset that’s more open to abundance or romance – but it’s not a magic wand. Be wary of any incense that’s exorbitantly priced just because it’s labelled with grand promises.

Often, you can find the same natural ingredients (e.g. jasmine for love, or cinnamon for prosperity) in a normal pack of incense without the markup. In other cases, those pricey “intention” sticks might even be synthetic (ironically undermining the spiritual aim). Focus on quality and tradition over hype. A pure frankincense or sandalwood will do more for your spirit than a chemically scented stick claiming to manifest cash.

In summary, choosing quality incense ensures that your meditation or cleansing ritual is supported by pure, positive energy. It’s an investment in your practice’s effectiveness – and in your own well-being, since you’ll be breathing it in! Now, with this savvy sense of what makes a great incense, let’s move on to some product guidance: what are the best options out there, and which one stands out as the ultimate incense stick for spiritual use?

Finding the Best Incense Products for Your Practice

Walking into the incense aisle (or browsing online) can be a bit overwhelming – so many scents, brands, and forms of incense vie for attention. To make it easier, start by narrowing down what you want from your incense. Are you primarily using it to accompany meditation sessions? To cleanse your home periodically? For a specific ambiance like yoga, prayer, or stress relief? Having a clear intention will guide your choice of scent and type.

For example, lavender or chamomile sticks might be lovely for meditation and sleep, while sage or copal incense might be favoured for heavy-duty space cleansing. However, across almost all spiritual uses, one type of incense consistently earns praise for its deeply grounding, purifying, and transcendent qualities: frankincense.

Kohẓen’s Real Frankincense Incense Sticks: Made from Hojari Frankincense in Oman

When it comes to choosing the best of the best, our top recommendation is Kohẓen’s Real Frankincense Incense Sticks. This incense exemplifies everything a spiritual practitioner could want: it’s 100% natural, profoundly aromatic, long-burning, and rooted in ancient tradition. In fact, these sticks are made in Oman from genuine Hojari frankincense – often considered the highest grade of frankincense in the world. Hojari frankincense comes from the Boswellia sacra trees of Dhofar (southern Arabia), harvested in small droplets of resin that have been used in sacred ceremonies for thousands of years.

What Kohzen has done is take that pure resin and craft it into a convenient stick form, without adding any synthetic perfumes or charcoal. The result is extraordinary: when you light one, you’re greeted by the bright citrus and soft pine notes characteristic of real frankincense, followed by a warm, honey-like sweetness as it continues to burn. The scent is often described as “churchy” or deeply spiritual – indeed it’s the same aroma you’d smell wafting through an old cathedral or temple, but now in your own living room.

Why do we make this frankincense stick the focal point?

Simply put, it delivers an experience that surpasses ordinary incense products on multiple counts:

- Authenticity of Aroma:

Because these sticks contain actual frankincense resin (not just an oil or synthetic imitation), the fragrance is wonderfully authentic and multi-layered. As one reviewer put it, “the scent is pure, potent and feels truly calming, filling your space with positive energy.” When you burn one, it’s like tapping into an ancient ritual – the room gradually smells like a sacred sanctuary. In contrast, many so-called “frankincense” incense on the market have never been near a frankincense tree; they’re usually perfumed sticks that might smell vaguely sweet or woody, but lack that recognisable sacred scent. Once you experience the real deal, those cheap imitations will feel flat by comparison. Kohzen’s frankincense sticks have a sparkling citrus-pine top note (a signature of Hojari resin) and no cloying, perfumey undertone at all. There’s nothing chemical in the smoke – it’s the same kind of pure incense that ancient monks and priests would use to uplift prayers. If you close your eyes while it’s burning, you could imagine yourself in a holy place. - Clean, Long Burn:

Each Real Frankincense Incense Stick burns for about 90 minutes, which is remarkably long for an incense stick. And it does so cleanly – you’ll notice a gentle pale smoke (no billowing black clouds, no harsh charcoal smell). This means you can use it in a small flat or meditation room without overwhelming the space. The sticks are a bit thicker and denser than standard joss sticks, owing to all that resin, which is why they last so long. A neat feature is that you can extinguish and relight a Kohzen frankincense stick later, and it won’t smell bitter or “used” when you light it the second time. That’s a sign of high quality. Many lower-grade incense sticks, if you try to save half for later, will stink when relit (or just refuse to stay lit). With these, you have the flexibility to do a short session or a long one. They also produce minimal ash that tends to drop in a neat, compact way – no messy crumbling. - Spiritual Potency & Calm:

Frankincense has long been valued for its spiritual potency – it’s associated with purification, protection, and meditation across numerous cultures. Users of Kohzen’s sticks often report a notable sense of peace when burning them. It’s not just about a nice smell; it’s about how that resinous aroma shifts the energy. Because the scent is so pure and natural, it doesn’t just mask odours or add fragrance – it seemingly transforms the atmosphere. If you’re doing mindfulness practice, the gentle resinous smoke can deepen your breathing and encourage a more meditative state (indeed, as mentioned earlier, there is scientific reasoning behind frankincense’s calming effect). If you’re performing a cleansing ritual, frankincense has that ancient reputation of banishing negativity and calling in a divine presence. In practical terms, people often describe that after burning these sticks, the room feels lighter, calmer, and even “blessed.” It’s the kind of incense that both scent-lovers and spiritually sensitive individuals appreciate for its high vibration. - Quality & Trust:

Kohẓen, is a brand known for sourcing frankincense directly from Omani harvesters and upholding ethical standards. There’s a comfort in knowing that what you’re burning is not only good for you, but also supports traditional communities and is sustainably harvested. Each tube of the Real Frankincense Incense Sticks comes with a handful of sticks (5 or 10 per pack), and a portion of proceeds supports humanitarian aid in West Asia. Our incense isn’t a mass-produced commodity – it’s an artisanal product born of a specific heritage. In a world of dime-a-dozen incense brands, ours stands out as something crafted with integrity. And while it might be a bit pricier than the $2 bargain incense at your local market, the difference is evident from the moment you open the package. You won’t burn through them as quickly either, given each stick’s length and burn time

Our Deep Dive: Kohẓen Real Frankincense Incense Sticks made with Royal Hojari: A Comprehensive Review

Now, you might wonder: “Is this the right incense for me?” Indeed, personal preference for scent plays a role. Frankincense has a resinous, slightly citrusy incense profile; if you absolutely know you dislike “church incense” smell, you might lean towards other natural options (like a high-grade sandalwood stick, or a floral like jasmine for meditation).

However, even those who aren’t familiar with frankincense often fall in love with these sticks once they try them – it’s a gentle, not overpowering aroma, and it creates an aura of clarity and sacredness that’s hard to match. It’s also universally appropriate: it won’t clash with any particular tradition or intent. You can use frankincense incense for practically anything – mindfulness meditation, yoga, chanting, prayer, space clearing, or simply to unwind after a stressful day. It’s like the multi-tool of spiritual scents.

(If you’re ready to experience them, you can find Kohzen’s Real Frankincense Incense Sticks on their official site or Etsy store – they often have deals for multi-packs, which is great because you will likely want more once you’ve tried them!)

A Note on Other Great Incense Options

While the frankincense stick above is our top recommendation (and the focal point for a truly elevated practice), it’s worth mentioning that there are other wonderful natural incenses you might explore, especially if you like to rotate scents or target specific vibes:

- White Sage or Palo Santo:

For those specifically interested in energy cleansing, you can’t go wrong with these classics. White sage smudge sticks, when sourced ethically, are powerful at clearing out negativity from a space. Palo santo (holy wood) from South America has a sweet, woody fragrance and is often used to welcome positive energy. They don’t burn as continuously as incense sticks (you have to relight sage bundles frequently), which is why many people complement smudging with incense like frankincense that continues to smolder. Some incense brands even make sage or palo santo incense sticks (using the real oils/essence) as a convenient alternative to burning the raw plant. Just ensure they are natural and not “scented” with synthetic versions. - Sandalwood:

Regarded as a meditation aid in many Eastern traditions, real sandalwood incense has a warm, soft, woody aroma that is deeply comforting. It’s excellent for creating a tranquil atmosphere and is often used in Buddhist and Hindu practices. High-quality sandalwood sticks (for example, authentic Mysore sandalwood or Japanese ones like Baieido or Shoyeido brands) can be a bit expensive, but the aroma is unrivaled for inner peace. If you prefer something less resinous than frankincense, sandalwood might be your go-to for daily meditation incense. - Lavender, Jasmine, or Rose:

If your focus is on relaxation, sleep, or heart-centred practices, natural floral incense can be lovely. There are incense sticks made with real lavender buds, jasmine sambac, or rose petals/essence. These tend to produce a gentle, sweet fragrance that can soothe emotional tension. Just be careful – florals are where a lot of synthetic fragrance sticks try to pass as natural. Look for indications that essential oils or actual flower powders are used. A true lavender incense, for instance, will smell herbaceous and not like a bottle of perfume. - Myrrh or Copal Resins:

In the realm of resin incenses, myrrh (often paired with frankincense) and copal are other spiritually potent choices. Myrrh has a grounding, bittersweet aroma used historically for protection and healing, and copal (a resin from the Americas) has a bright, clearing smoke often used in ceremonies. These can be burned on charcoal or found in stick form blended with wood powders. They are great for deep cleansing and ancestral or devotional work. If you enjoy frankincense, exploring its “cousins” like myrrh might enrich your practice too.

Whichever incense you choose, remember our earlier advice: opt for natural and high quality. It truly makes a difference. One way to ensure you’re getting quality is to buy from reputable suppliers or brands known in the spiritual community (reading reviews can help). Sometimes small metaphysical shops carry hand-made incense that’s excellent. And if you’re buying online, look for clear descriptions of ingredients. Don’t hesitate to treat incense like any other wellness product – check what’s in it, where it’s from, and if the maker seems trustworthy.

Watch Out For Gimmicks (Choose Substance Over Hype)

Before we wrap up, it’s worth reiterating a gentle warning about the more “gimmicky” incense products out there. In recent times, we’ve seen incense marketed as almost supernatural solutions – e.g. sticks that promise to attract wealth or cause weight loss just by lighting them. It can be tempting to believe there’s a shortcut like that, but at best these are clever marketing with a nice smell, and at worst they’re overcharging you for incense that’s no different (or inferior) to standard ones.

Fact Check: burning a “money attraction” incense stick isn’t going to drop £1000 in your lap. What it can do is put you in a positive, abundance-focused mindset – but so can a good meditation with any pleasant incense you love. Likewise, a “weight loss” incense might claim to reduce stress (since stress can affect weight), but you could get the same benefit from burning a calming lavender or frankincense while doing your workouts or meal prepping, without paying a premium for the label.

We’re not here to knock anyone’s product, and certainly the idea of combining aromatherapy with intention-setting is valid. Just know that you don’t need a special branded stick for each life problem. What you need is your own intention and a supportive atmosphere. Incense can absolutely be part of that support – but you are the main ingredient in your spiritual growth, not any object. By choosing incense that is authentic and resonates with you, you empower your practice far more than by choosing one because it has a flashy claim.

So if you come across incense that seems overpriced due to marketing, you now have the knowledge to discern if it’s truly something unique or just repackaged common ingredients. Ghosting those low-quality competitors (the ones that puff up claims but use perfume on cheap sticks) is as simple as not giving them your attention or money. Instead, invest in incense that has real substance: pure ingredients, cultural wisdom behind it, and positive reviews from real users.

Closing Thoughts

During the serene dance of fragrant smoke, there is an invitation: breathe, slow down, and reconnect with the sacred. Whether you’re a seasoned meditator, a curious beginner, or someone seeking to energetically refresh your home, incense sticks offer a timeless aid. By now, you should feel confident about the basics – you know the difference between incense marketed as spiritual sticks, joss sticks and smudge sticks, you understand why natural incense is non-negotiable for a truly uplifting experience, and you’ve learned how to spot quality (and avoid the duds).

We’ve also highlighted Kohẓen’s Real Frankincense Incense Sticks as a standout choice that embodies what “the best” looks like: all-natural, steeped in tradition, highly effective, and loved by those who use it. Making this your go-to incense could very well elevate your meditation and cleansing rituals to a new level.

Light a stick in the morning as you do yoga or journal – the royal frankincense aroma gently fills the air, and you feel a wave of calm focus. Or in the evening, after a long day, you burn half a stick while soaking in a bath; as the soft smoke twirls, you sense the day’s worries clearing out, replaced by a subtle sense of sanctuary. This is the kind of experience quality incense can create. It’s not just about “smelling nice”; it’s about engaging with a tool that countless generations before us have used to connect with the divine, with nature, and with their own inner stillness.

As you incorporate these spiritual sticks into your life, do so with respect and intention. A small ritual of lighting incense can become a cherished habit of self-care and spiritual hygiene. Explore different scents and see how they affect your mood and space. You might reserve certain incenses for certain activities (perhaps sage for New Moon cleansings, jasmine for creativity sessions, frankincense for daily meditation – you create your own correspondences that feel right). Over time, the very act of lighting that stick will signal to your psyche that it’s time to enter a sacred mode.

Lastly, always ensure safety – never leave burning incense unattended and keep it away from flammable items or curious pets. Use a proper holder, and don’t forget to ventilate now and then. The goal is to enjoy the aroma, not to inhale smoke excessively.

We hope this guide has been both informative and empowering. The world of incense is rich and rewarding, bridging the earthy and the spiritual with each tendril of smoke. By choosing the best products and understanding their use, you set yourself up for truly transformative moments. Whether it’s a deep meditation, a peaceful home, or simply a mindful pause in a hectic day. Light your incense with love, and let your intentions rise with the smoke.